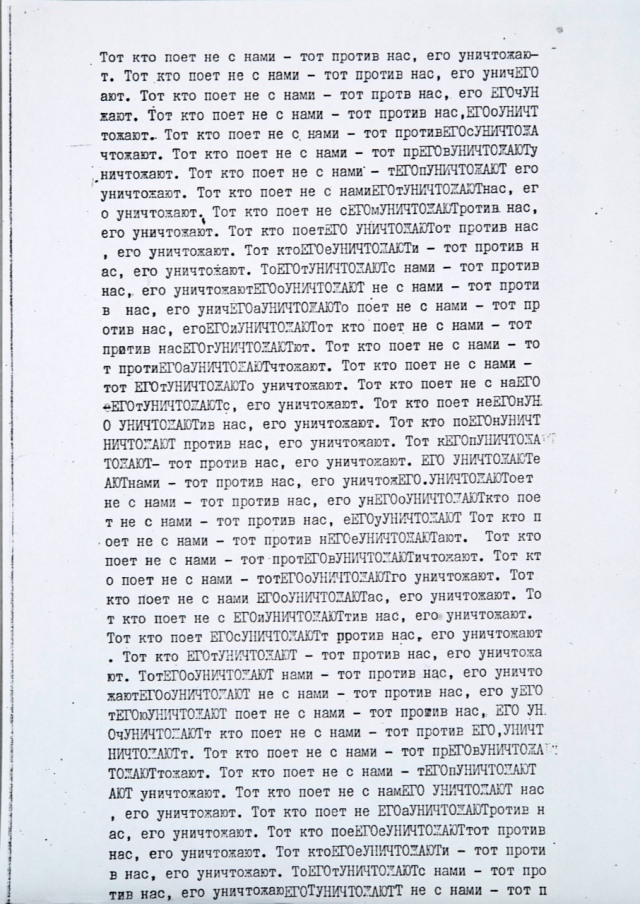

Dmitri Prigov, Tot kto poet ne s nami––tot protiv nas, ego unichtozhauiut [He Who Does Not Sing with Us Is against Us and Is Destroyed]. Typewritten text on paper. 29.6 x 21 cm. A-Ya Archive, Lettrist series. Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union, 071.001.027. Photo by Peter Jacobs. Reproduced with the permission of the Estate of Dmitri Prigov.

To recognize the diversity and historically and culturally inflected nature of conceptual writing, we would do well to take some Russian lessons. In this essay, I turn to a form of conceptual writing that developed in a radically different social, political, and historical context: the text-based works of Moscow conceptualism and in particular the writings of conceptual poet Dmitri Prigov. Emerging out of the social and political environment of the Soviet Union in the 1970s and early 1980s, Moscow conceptualism appropriated aspects of Western conceptual art, but also responded to very different institutional structures for art and contrasting understandings of the relationship between words and things. These differences can help us recognize the contextual and institutional framings that shape and are addressed by conceptual writing. Moscow conceptualism’s particular emphasis on literature and its literary conceptual practice contain lessons for how we understand the later rise of conceptual writing as a literary practice in the anglophone world. The Russian example reveals conceptual writing’s deep but still insufficiently acknowledged engagements with ideological discourse, literary and artistic institutions, and authorship.

Amongst other works, I take as an example two works from Prigov’s Stikhogrammy (Versogrammes, or Lettrist series), including Tot kto poet ne s nami – tot protiv nas, ego unichtozhaiut (He Who Does Not Sing with Us Is against Us and He Will Be Destroyed; pictured above). Here’s my take on the work:

Prigov emphasizes the promised destruction by having the capitalized phrase “ЕГО УНИЧТОЖАЮТ” (HE WILL BE DESTROYED) override the lowercase text diagonally from right to left down the page. The first part of the text, “He who does not sing with us is against us,” is an almost exact quotation from Vladimir Mayakovsky’s poem “Gospodin, ‘narodnyi artist’” (Mister “National Artist”), an attack on the Russian émigré opera singer Feodor Chaliapin published in the Soviet newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda in 1927. Combined with the meaning and literary allusion of the first quotation, the final phrase echoes the title of Maxim Gorky’s article “Esli vrag ne sdaetsia, – ego unichtozhaiut” (If the Enemy Will Not Surrender, He Will Be Destroyed), which appeared in the newspaper Pravda in 1930 – the year of Mayakovsky’s death – and was later quoted by Stalin in a statement issued during the Second World War. Prigov here performs the unconditional surrender of the poet to the state through the transformation of the writer into a machine-like producer who sings for the state (“with us”) by retyping a prescribed text. Underscoring the connection between the poetic word (which in Mayakovsky’s poem becomes “a bomb”) and totalitarian ideology, Prigov locates the origins of Stalin’s totalitarianism in the Russian avant-garde. Prigov invokes the Russian avant-garde through the citation of Mayakovsky, the echo of his innovative stepped line, and the geometrical abstraction of the concrete poem’s shape. He connects the avant-garde to Stalinism by having the geometrical abstraction emerge through the interplay of Mayakovsky’s ominous phrase and Gorky and Stalin’s capitalized words of total destruction.

Just as he connects totalitarianism to avant-gardism, Prigov inserts official discourse into the unofficial realm of the samizdat text, which was fetishized by many in the Soviet intelligentsia. By repeating phrases on a typescript page, he links the repetitive clichés and slogans of official propaganda to the retyping required for the reproduction of samizdat texts. Prigov presents non-literary appropriated material and discourses within the institutional structures of samizdat literature. Though dependent on the cultural and historical specificities of samizdat, Prigov’s literary framing of non-literary texts anticipates anglophone conceptual writing such as Kenneth Goldsmith’s Sports, Traffic, and The Weather, Rob Fitterman’s Metropolis series, Vanessa Place’s Statement of Facts, or even Bruce Andrews’s less strictly ordered appropriation of media and political discourses in precursor works like Give Em Enough Rope. Like Komar and Melamid’s verbatim reproduction of slogans, Prigov’s approach also presages Vanessa Place’s emphasis on repeating “the discourse of the master.” More humorously and perhaps even more mercilessly than Place, Prigov alerts us to the implicated relation of conceptual writing and the avant-garde as a whole to discourses of power.